For the last day or so, I’ve been thinking a lot about programming and testing, about collaboration and walls, and about where this may all be going. This post is the start of my mental exploration of the subject.

In the beginning…

In How We Test Software at Microsoft, we told the story of Microsoft hiring our first tester, Lloyd Frink. Lloyd was a high school intern, and his job was to “test” the Basic compiler by running some programs through the compiler and make sure they worked. That was 1979, but full time testers didn’t show up at Microsoft until 1983. I have no recollection or knowledge of what was happening in the rest of the software industry at that time, but I imagine it was probably the same. Since then, Microsoft has hired thousands of testers (we currently employ over 9000), and the industry has hired a kazillion (yes, a made up number, because I really have no way of guessing) software testers (regardless of title).

Now, in the last several years, many teams (including some inside of Microsoft), have moved to the “whole team approach” – where separation of testing and programming roles are blurred or gone (the activities will always exist). Even on teams where separate roles still exist, there is still a significant amount of blurring between which activities each role does as part of their job (for example, I, like many of my test colleagues, make changes to product code, just as many programmers on the team create and edit test code).

The Wall

The metaphorical “wall” between programming and testing is often quite high (as in programmers write code, then throw it over the wall to testers; who, in turn, throw the bugs back over the wall to developers, who make fixes and start the wall-chucking process over again). Lloyd was hired to catch stuff thrown to him over the wall, and I think it’s a fair argument to say it would have been more efficient for developers to run those tests as part of a check-in suite (assuming, of course, they had such a thing).

To be completely transparent, a wall on my team still exists – it’s just a much shorter wall. There are still expectations of programmers and testers that fit into the typical roles, but collaboration and code throwing don’t occur often.

Infection

Elisabeth Hendrickson speaks often of being “test-infected” to describe programmers who “get” testing (I believe the term was coined by Erich Gamma). I for one, can’t think of a good reason for a programmer to not have some test ideas in their head when they write code.

Similarly, I think that testers can benefit from being a bit “code-infected”. Before the self-preserving screams of oppression begin, let me note that I said testers “can benefit” from some code knowledge. I’m not talking about language expertise – a basic understanding of programming logic and some ideas on how computer programs may improve testing is usually plenty. It’s not necessary to know anything about programming to be a tester – I’m just saying it can help.

Beyond the disclaimer, it’s worth elaborating on the last two paragraphs here. I have had testers tell me that knowledge of code will adversely affect the “tester mindset” – that by knowing how to code, the tester will somehow utilize less of their critical thinking or problem solving skills. While I suspect this to be a false assumption, I have no proof of whether this is true or not. But I will hypothesize that if this is true (that code-infection adversely affects testing skill), then it’s just as likely that test-infection adversely effects programming ability. When I look at it this way, the answer clears up a bit. Take a moment to think about the best programmer you know. I’m fortunate enough to work with some really incredible (and some famous) programmers. Every single one of them is test-infected. Yes – I have no hard data, and zero empirical research, so I could be high as a kite on this, but I’d be curious to hear if anyone knows a great programmer who doesn’t have the ability to think at least a little bit like a tester.

Code Infected

So – let’s suppose for a few minutes that code-infection is beneficial for testers. Not even necessarily equally beneficial – just helpful. Is there such a thing as too infected? An old colleague of mine, John, once said,

“I’m not the best tester on the team, and I’m not the best programmer. But, of the programmers on the team, I’m the best tester, and of the testers, I’m the best programmer”.

Which role should John be in? On your team, would he be a programmer, or a tester? Is it a clear cut decision, does it depend, or does it even matter? Is John a test-infected developer, or a code-infected tester? Does it matter?

I think the answer to the above questions are either “It depends”, or “It doesn’t matter”, so let me ask a different question. Do you want a team full of John’s? Maybe you do, or maybe you don’t (or maybe it depends), so let me rephrase yet again in the form of a quick thought experiment.

An experiment

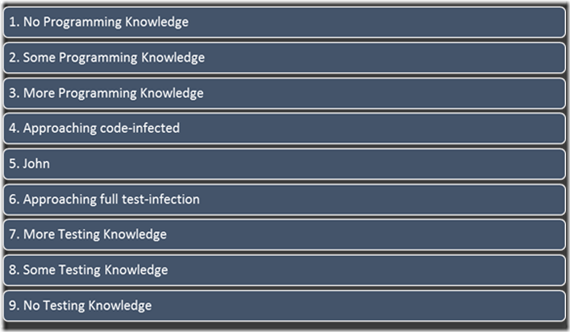

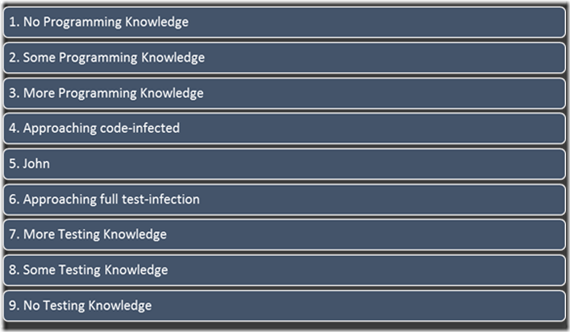

You are forming a nine-person team to make a super cool software application. You get to build a dream team to put it together. On a scale from 1-9, where a 1 is a tester with zero knowledge of programming, a 9 is a developer who can’t even pronounce “unit test”, and a programmer / tester like John is a 5 – which employees do you hire (note that all of these people get paid the same, work the same hours, get along with each other, etc.).

To be fair, I don’t think there’s a “right” answer to this question, but we can certainly explore some options of what would be more or less “right”. One option is to (conveniently) select one of each type. Then you get infection-diversity! However, I’m betting that most of you are thinking, “There’s no room on my team for developers who don’t write unit tests!” So, is “some” testing knowledge enough? Is it possible to have too much? If I hire 7’s and 8’s, do I eventually want them to have more testing knowledge? If that’s the case, should I just hire 5’s and 6s instead?

And what about testers? Remember, that code-infected doesn’t necessarily mean that the testers are code-monkeys cranking out tools and automation all day long – it just means that they have (varying levels of) programming skills as part of their available toolbox. The context of the product may have some influence on my choice, but if you agree that some programming knowledge can’t hurt, then maybe a 2 is better than a 1. But is a 3 better than a 2? “I suppose that “better” depends, but to me, it’s a worthwhile thought process.

But that’s not right…

If you’ve read this far without jumping down to comments to yell at me, let me admit now that I’ve led you in a bad direction. The exercise above sort of assumes that as you gain testing ability, you lose programming ability (and vice-versa). That’s not true in the real world, so let’s try a bit of a twist and see if we can be slightly more realistic. For this exercise, you have the $1,000,000 of salary to spend on a maximum of 10 employees. You have the following additional requirements:

- An employee can have a “programmer” rating of 0-10, where 0 is can’t even write a batch file to 10 where they dream in algorithms.

- Similarly, an employee has a “tester” rating of 0-10 where 0 is no knowledge of testing, and is at least the best tester you’ve ever dreamt of.

- Minimum salary is $50k, and the maximum salary is (arbitrarily) $160,000.

Because context is important, let’s say the app is a social networking site with clients for phones and tablets, as well as a web interface. Your exercise (if you want to play) is to think about the type of people you would use to staff this team. One option, for example, is to have five developers, each with a 10 rating (5x$100,000), paired with 10 testers who also each have a 10 rating (5x$100,000). Another option would be to have 6 developers, each with a 15 rating (e.g. 9-dev and 6-test for 6x$150,000=$800,000) paired with 4 testers, each with a 5 rating (4x$50,000-$20,000). The choice is yours, and there’s no right answer – but I think the thought exercise is interesting.

I’ll close this post by saying that I really, really hate sequels and series when it comes to blog posts (and I’ll add an extra “really” to that statement when referring to my own posts). But there’s more to come here – both in my thoughts on testing and programming, and in more thought exercises that I hope you will consider.

More to come.